If you love printed objects the way I do, you have probably stared at a label or a book cover and wondered how it was made. This guide will help you answer that question with confidence.

You will learn how gravure printing looks and feels in the real world. You will also learn a few fast tests that you can do at your desk without special lab gear.

Here is what you will be able to do by the end.

- Spot the core visual cues that separate gravure from offset, flexo, litho, and screen

- Use simple tools to check the surface and the edges of a print

- Read the clues that long runs leave behind on packaging films and foils

I will also share the mistakes that I made and explain to you the importance of raking light checks to look for the tiny cell structure that only gravure leaves. And a whole lot more.

Keep reading!

Tools You Will Need

You don’t need an array of expensive and professional tools to identify gravure printing as a beginner or enthusiast. A few simple tools will take you far. I keep these in a small pouch on my desk, and they have saved me more than once.

Loupe or Phone Macro Lens

A 10x loupe is perfect. A clip-on macro lens for your phone also works well. I use it to look for the tiny cell pattern that gravure creates. Under magnification the tone looks like a field of tiny bricks or honeycomb. Early on I tried to guess with my bare eyes and I kept missing those cells. The loupe fixed that instantly.

Small Flashlight for Raking Light

Shine light across the surface from a low angle. This reveals micro relief. Gravure often shows a soft valley effect in dark areas. I forgot this step on a winery label once and called it offset. I went back, used raking light, and saw the subtle topography that proved it was gravure.

Plain cotton pad for a gentle rub test

Very light pressure tells you how the ink sits. Gravure ink feels supple and bonded. Screen ink often feels thick. Never scrub. One soft pass is enough. I ruined a proof years ago by rubbing too hard. Learn from me and be gentle.

Clean Gloves and a Smooth Table

Gloves keep oils off the print. A flat table stops warping and glare. Good handling protects the clues you are trying to read.

The Core Idea Behind Gravure

Gravure is a form of intaglio printing, which means the image lives below the surface. The heart of it is the engraved cylinder. Think of the cylinder as the image carrier filled with thousands of tiny printing cells.

During printing those cells hold ink, the doctor blade wipes the cylinder’s surface clean, and the impression roller presses the paper or film into the cells so the ink transfer happens.

Two small numbers control most of what you see. Cell depth and cell opening. Together they decide how much ink leaves the cylinder and how strong the ink density looks on the substrate. Deep cells carry more ink for rich shadows. Shallow cells carry less ink for highlights and smooth ramps.

When I first learned gravure, I kept chasing color by adding pigment. The prints still looked starved. My mentor pointed me back to the cells. We measured depth, checked a few test bands, and the color opened up without extra ink at all. That lesson stuck.

In gravure, geometry rules. Get the cells right, hold a clean doctor blade, keep steady pressure in the nip, and the substrate transfer will stay smooth. Once you feel that balance, gravure becomes predictable and beautiful.

The Plate Mark Test on Fingers

When I examine a print on cotton paper, I start with the plate mark. Gravure on paper often leaves a shallow rectangular emboss where the plate met the sheet.

I hold the print at eye level and let light graze across the surface. A gentle step appears at the border. Then I run a gloved fingertip across the edge. I feel a tiny dip where the plate sat during the pass through the press.

Here is what to look for.

- A faint rectangle around the image that looks pressed into the sheet

- A smooth transition rather than a sharp cut that could be a trimmed edge

- Paper fibers that appear slightly compressed near the border

A few warnings help. Not every gravure piece on paper shows a strong plate mark. Heavy trimming can remove part of it. Thick mounts can hide it. Some presses use tight tolerances that leave only a whisper of an impression.

Packaging films and foils are a different game. Most do not show a plate mark at all. The web never sees a rigid plate edge the way art papers do.

Early in my career I wasted time hunting for a plate mark on a snack pouch until I learned to switch tactics. On film, I skip the plate edge and move straight to raking light and the loupe.

The raking light test is important in identifying gravure printing. And doing it correct is like winning half the battle without much of effort. The next section describes how to do it.

Raking Light Test For Surface Topography

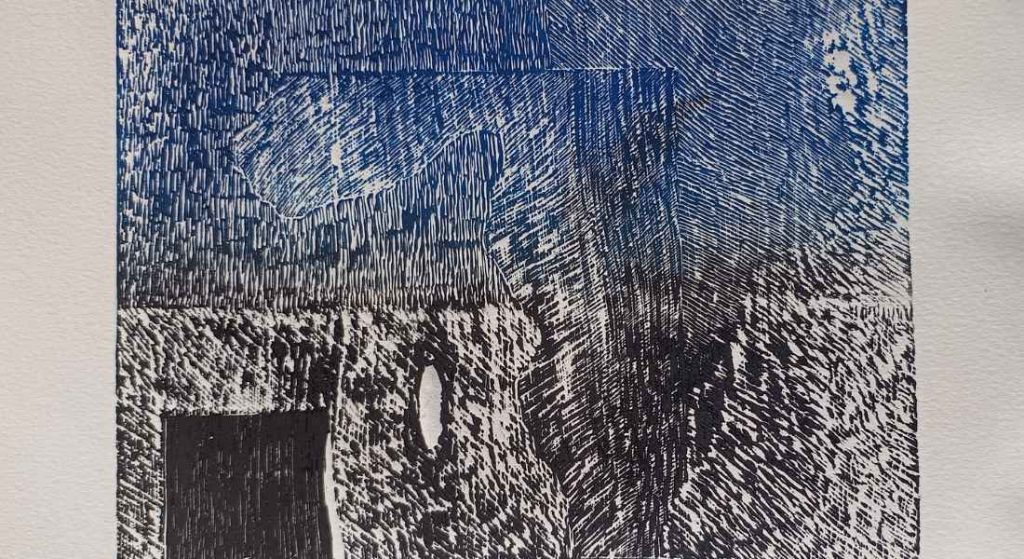

Raking light is my favorite quick test. I place the piece on a flat table, turn off overhead glare, and sweep a small flashlight across the surface from a low angle. While doing so the shadows reveal the texture that straight-on light hides.

But you’d need to read well what the shadow shows you.

Here is what gravure often shows. In dark passages you see gentle micro valleys where the paper or film pulled ink out of the cells. The surface looks calm and even, not pebbled.

But the rich areas feel velvety rather than glassy and the highlights roll off smoothly without a gritty sparkle.

When I compare this to other methods I find that the offset usually stays flat no matter how I tilt it.

I compare this to other methods as I look. Offset usually stays flat no matter how I tilt it. Screen printing often shows a crisp ledge where thicker ink sits on the sheet, and the light will catch that edge with a bright rim. Flexo can reveal a soft orange peel in large solids, especially when the plate was a touch too soft or the pressure was high.

Gravure tends to fall between all of these. It shows depth without harsh relief, and the light glides over it instead of breaking on ridges.

I once misread a cosmetics carton because I checked it under bright overheads only. When I came back with raking light, the valleys in the black panel appeared at once. That small habit change has saved me many times.

Loupe Inspection Of Edges And Lines

The light test isn’t enough, there’s more to do when it’s done.

When the light test suggests gravure, I reach for a 10x loupe. I steady the piece on a flat surface, brace my wrist, and bring the lens down until the image fills my view. My goal is to see how tone is built and how edges behave.

In gravure, continuous tone comes from tiny cells that sit below the surface. Under the loupe those cells look like little bricks or a tight honeycomb.

I don’t have a camera or images to show such a micro-shot, but I am trying my best to describe it in my words so that you know what to do when checking it out, but I digress.

Now coming back to the topic. In a smooth sky or a soft shadow you will not see halftone dots like offset. You will see a field of micro cells that hold more or less ink depending on depth.

When the cells are uniform, the tone feels even and clean. When the cells are clogged or damaged, the tone looks blotchy. I learned that lesson the hard way on a tight deadline. I blamed the ink mix at first, but the blotches were coming from grit lodged in the cells. We cleaned the cylinder and the tone snapped back to smooth.

Next I walk the loupe to the edges. Gravure edges often show a fine sawtooth because the cell pattern reaches the boundary of a letter or a shape. It is a delicate texture, not a harsh stair step. If I see this gentle tooth, I note it.

Offset edges look smooth and vector sharp under the same lens. Flexo edges can swell a little, which creates a halo. Screen edges tend to mirror the stencil and may reveal a slight jag on curves. Gravure sits apart. The edge is crisp, yet it still whispers the rhythm of the cells.

For line work I look at cross hatching and micro type. Gravure can carry very fine lines without breaking into dots. Cross hatching stays crisp and the spaces between lines remain clear.

If the press ran well, there is no moiré in those tight textures. I once chased moiré for an hour on a décor film only to learn the art had a low resolution file baked in. The cylinder was perfect. The loupe told the truth and saved the shop from grinding metal for no reason.

I finish with one sweep across highlights and deep shadows. Highlights should show smaller or shallower cells and they should not drift into grainy sparkle. Shadows should feel full and connected with no laddering. That smooth shift from light to dark is the signature I trust.

When the loupe shows it, I am ready to call it gravure.

Final Words

There you have it, the easy to find cues that will tell you if the printing is gravure. Identifying it is not rocket science. However, you would need to have a good eye to spot the patten under shadows, textures, and the smoothness on the surface.

To find out more about gravure printing, you can check my post here.