Printmaking is an art form where artists create an original image on one surface (called a matrix or plate) and reproduce it on another surface. If you are a printing professional or collector, you might be interested in this short guide that will give you a brief overview on the types of printing.

For collectors and art professionals, the appeal of printmaking lies in these visual and tactile qualities that differ with each technique. The major types of printmaking are generally categorized as relief, intaglio, planographic, and stencil methods. But there are unique types of printing such as collagraphy and digital printmaking which fall into the category.

The theme that runs across in all the types of printing is that each type has distinct processes and results, from the bold, raised lines of a woodcut to the velvety depths of an etching. I will throw some light on them by giving you separate sections of tactile qualites, visuals, and examples with respect to each type of printmaking.

Let’s delve into each, understanding not just how they are made but also how they look and feel, which is crucial for appreciating prints from a collector’s perspective.

1. Relief Printing

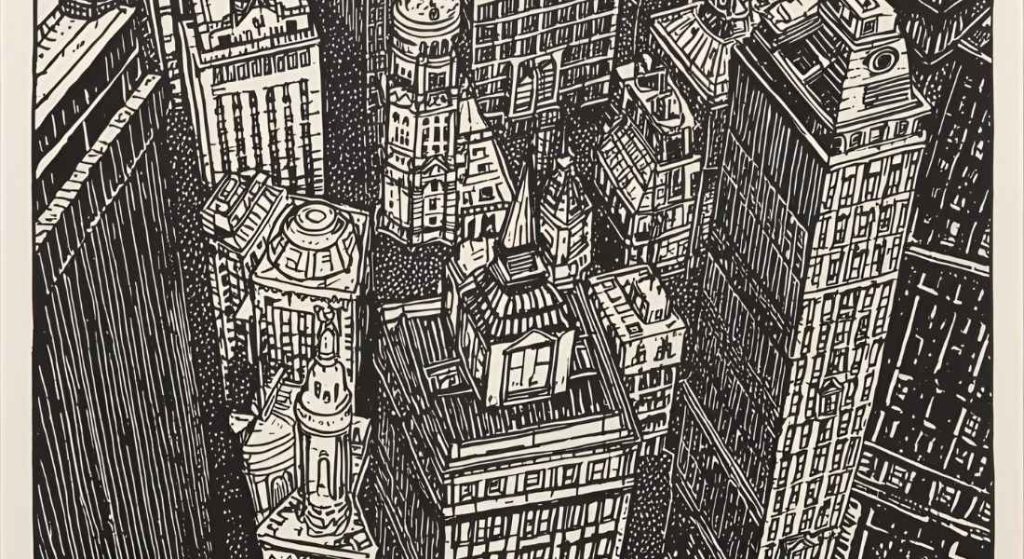

Relief printmaking is one of the oldest methods of making prints. In relief printing, the artist cuts or carves into a block or plate, removing the areas that will remain white (uninked) in the final image. Ink is rolled onto the raised surface that remains. When paper is pressed against the block, the inked areas transfer to produce the print.

Common relief matrices include wood (for woodcuts) and linoleum (for linocuts). This technique dates back to ancient China and became prominent in Europe by the 15th century. Albrecht Dürer elevated woodcut printing with highly detailed works and patterns that became the gold standard of relief printing.

Visual Characteristics

Relief prints are known for bold, graphic lines and high contrast imagery. Because the ink sits on the surface of the block, printed lines and shapes tend to have crisp edges.

You can often see evidence of the carving process, in the form of knife and gouge marks, which gives relief prints a distinctly hand-made character.

In woodcuts, the texture of the wood grain might appear in the print, adding a rustic pattern to the image. Linocuts, by contrast, have a smoother look since linoleum has no grain. Visually, relief prints may remind you of traditional illustrations or posters with flat areas of color.

Tactile Qualities

If you run a fingertip gently over a relief print (though collectors usually handle prints with great care!), you might feel slight unevenness where the ink lies.

Traditional relief prints on dry paper typically do not emboss the paper deeply, but the inked areas can have a subtle raised texture because the ink sits on top.

Unlike intaglio prints, there is no plate mark indentation from a plate’s edge. Instead, any borders or outlines come from the carving itself. Overall, relief prints feel flat to the touch, except where heavy ink might leave a tiny ridge at the edges of shapes.

Examples of Relief Printing

Woodcut prints often showcase strong contrast and simplified shapes . The best examples that I can give is of the famous Japanese ukiyo-e woodcuts or German Expressionist black-and-white prints. Linocuts can achieve similar effects.

Many beginners start with linocut because the material is easy to carve. Contemporary artists use relief for everything from art prints to textile designs because of its bold impact.

2. Intaglio Printing

Intaglio printing is essentially the opposite of relief. In intaglio, the design is incised into a metal plate (usually copper, zinc, or steel) by carving or etching with acid. Ink is applied over the plate and then wiped off the surface, leaving ink only in the recessed lines or areas.

To make a print, artists run a damp sheet of paper is placed on the plate and run through a high-pressure press, which forces the paper into those ink-filled grooves, transferring the image. Intaglio techniques include engraving, etching, drypoint, aquatint, and mezzotint. These methods distinguishes how the lines or tones are created on the plate.

Visual Characteristics

Intaglio prints are prized for their fine detail and rich tonal range. Because the lines are cut into the plate (whether by a tool in engraving or by acid in etching), they can be incredibly sharp and precise.

Intaglio methods can produce everything from delicate hairline scratches (as in drypoint or faint etching lines) to velvety blacks (as in mezzotint or deep etching). Another hallmark of intaglio prints is the plate mark, which is a rectangular embossed outline on the paper, left by the edge of the plate when it’s pressed into the paper.

Collectors often love seeing a plate mark; it is a tactile sign that the print was made with an intaglio process and an intaglio press. The printed lines and areas from intaglio have a slightly raised ink surface that you can feel, because the thick, damp paper literally pulls the ink out of the grooves and onto itself. This gives intaglio prints a richly textured feel in the darkest areas. Visually, intaglio prints can achieve subtle shading and fine cross-hatched details that are difficult to match in other print types.

Tactile Qualities

When you handle an intaglio print, you may notice the paper has a depressed outline (the plate mark) around the image where the plate was pressed in. Within the image, heavily inked lines or areas (such as in an aquatint) might feel slightly raised or thicker due to the layers of ink.

Intaglio prints often use thick, soft paper (often dampened during printing), which gives the final print a plush, almost fabric-like feel. Running a finger (carefully with gloves) over an intaglio print, you can sometimes detect the slight ridges where ink has been pushed out of engraved lines, or feel the difference between heavily shaded areas and lighter areas. The overall surface has gentle undulations corresponding to the artist’s engraved or etched work.

Examples of Intaglio Printing

A classic engraved intaglio print might be a vintage banknote or an old map with full of extremely fine lines. In art, Albrecht Dürer’s engravings from the 16th century or Rembrandt’s etchings show the astonishing detail and expressive line work intaglio can achieve.

Intaglio techniques are also often combined; for instance, an artist might use etching for line work and aquatint for shading on the same plate.

For collectors, intaglio prints (like etchings, engravings, etc.) are often considered highly valuable because of their craftsmanship and the tradition of print connoisseurship associated with them. Even today, security documents and currency use intaglio for its fine detail and tactile quality.

The differences between relief and intaglio printing are laid out on my post here.

3. Lithography (Planographic Printing)

Lithography is the principal example of planographic printmaking, where the printing surface is completely flat (unlike raised relief or incised intaglio). Invented in 1798 by Alois Senefelder, lithography is based on a simple chemical fact. And that is oil and water do not mix.

In lithography, the artist draws an image onto a smooth stone (traditionally limestone) or metal plate using a greasy medium (like a special crayon or ink). The drawing is then treated with a chemical solution (often gum arabic and a weak acid) that causes the drawn greasy areas to accept ink and the blank areas to repel ink.

When the stone or plate is inked with a roller, the ink sticks only to the greasy drawing. A piece of paper is then pressed on top, transferring the inked drawing to create the print.

Visual Characteristics

Lithography is known for its ability to capture a wide range of tones and very fine detail, closely resembling the original drawing or painting made on the stone. Artists can draw with crayons, pens, or even washes of tusche (an oily ink) on the stone, so the printed result can have soft shading, rich textures, and continuous tones that are difficult to achieve in other print methods.

A lithograph can look almost indistinguishable from a charcoal drawing or a watercolor wash, depending on the technique. Unlike relief or intaglio, there are no obvious directional lines from carving tools. The lines and shades in lithography look drawn or painted naturally.

Colors can be used in lithography by drawing separate stones or plates for each color (this is how many vintage posters were made in the 19th century). Because the surface is flat, lithographs don’t have the punched-in plate mark of intaglio or the obvious raised ink of relief; visually they often appear very smooth.

Tactile Qualities

A well-printed lithograph on quality paper will feel relatively smooth to the touch. There is usually no embossed plate mark (especially if done on a thick stone or if the paper covers the stone fully), and the ink lies in thin layers on the paper. If multiple layers of color are printed, you might feel a slight layering where inks overlap heavily, but generally lithography ink is not as thick as relief or screenprint ink. T

he paper surface remains flat since the printing does not require extreme pressure or digging into the paper. You won’t feel carved edges or deep textures. Instead, any texture comes from the grain of the stone or the drawing material. For instance, lithographic crayon can create a grainy texture in the printed image, but to the fingertips the print still feels flat, just like a page from a book.

Examples

Many artistic posters and fine art prints are lithographs. For example, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s famous Moulin Rouge posters were lithographs, capturing painterly swathes of color. Ansel Adams, the photographer, also created lithographs of some photographs, leveraging the technique’s ability to render continuous tones.

Collectors appreciate hand-drawn lithographs because they carry the spontaneity of the artist’s original drawing. In contemporary art, lithography is prized for producing limited edition prints of artworks that might look as detailed as a pencil or ink drawing. Because of the planographic process, there is a certain magic in how the greasy drawing on stone translates into a printed image with all its subtle shades intact.

4. Screen Printing (Stencil)

Screen printing, also known as silkscreen or serigraphy, is a stencil-based printmaking method. Unlike the other processes, in screen printing the ink is pushed directly through a mesh screen that has been prepared so that certain areas are open (allowing ink to pass) and others are blocked.

The screen is often a finely woven fabric (originally silk, now synthetic) stretched tightly over a frame. The artist creates a stencil on the screen with paper cut-outs, or more commonly with a photo-emulsion process that blocks parts of the mesh.

To make a print, the screen is placed over paper (or fabric, or any substrate), and a layer of ink is pulled across the screen with a squeegee. Ink passes through the mesh openings and onto the material below, printing the design in those areas

Visual characteristics

Screen prints are celebrated for their bold, vibrant areas of color. Because the process allows a thick layer of ink to be deposited, colors in a silkscreen print tend to be strong and opaque, often with crisp edges where the stencil blocks the ink. This technique is great for graphic designs, posters, and artwork that requires solid fields of color.

Screen printing can produce images with a commercial graphic quality. I can remember that it was famously used by Pop Art icons like Andy Warhol, for example in his multicolored celebrity portraits and soup cans.

Each color in a screen print is usually printed with a separate screen, so many screen prints have a limited color palette with distinct layers of color rather than blended tones (though advanced techniques can create gradients). Registration (aligning the screens) is key, and when done well, a screen print has very clean alignment and uniform color fills.

Tactile qualities

One of the first things you notice touching a screen print is the feel of the ink. Screen printing ink often sits on the surface as a slightly raised layer. For example, if you rub your hand gently across a silkscreened poster or t-shirt, you’ll feel the difference between the printed areas (which might feel a bit plasticky or thicker) and the unprinted paper or fabric.

On paper, heavy ink areas might even produce a slight relief you can see and feel, especially if multiple layers of ink are superimposed. The overall paper, however, remains flat – screen printing doesn’t indent the paper like intaglio. Instead, it adds on top. High-quality artistic screen prints use inks that can be quite velvety or matte to the touch, which is pleasant.

Textiles printed via silkscreen obviously have a more tactile ink feel (like the design on a printed t-shirt). For collectors of paper prints, the layered ink can give a satisfying texture when viewed at an angle or under light, as each color layer catches gloss slightly differently.

Examples

Aside from Warhol’s works, many modern artists and street artists use screen printing to create limited edition prints. It’s also used in printing gig posters, graphic art, and even high-end fine art editions because of its capacity for vivid color.

In the world of collectibles, a hand-pulled screen print of a favorite artist or band poster is valued for its craftsmanship. In those prints you can often literally feel the ink, reminding you it was made by a person pulling a squeegee.

Screen printing is also extremely versatile beyond paper. It’s used on canvas, clothing, glass, metal, and more, which speaks to its strong, hard-wearing application of ink.

5. Monotype and Monoprint

Monotypes and monoprints are sometimes grouped with the major printmaking categories, but they are unique in that they produce one-of-a-kind prints (hence “mono”).

In a monotype, the artist paints or inks an image on a smooth, non-absorbent surface like glass or a metal plate without any fixed lines or design etched into it. While the ink is still wet, a piece of paper is pressed onto this plate (often by hand or with a press), transferring the image.

It’s done because most of the ink transfers during the first step. And you generally can’t make make multiple identical copies. Because if you try then the ink transfer won’t take place during the second pull and you’ll get a faint “ghost” print at best.

A monoprint is very similar, except it starts from some repeatable matrix (like an etched plate or carved woodblock) that has a unique inking or collage that makes the print one-off. In practice, the terms are often used interchangeably, but the key is that each print is unique even if the process is partly repeatable.

Visual characteristics

Monotypes often look very painterly or experimental. Since the artist is essentially painting on a plate and then taking a transfer, the resulting print can have soft, blurred qualities or very delicate, flowing lines. Artists can also achieve effects like watercolor or oil painting in a monotype by making washes of color that print as translucent layers.

The beauty of a monotype is in its spontaneity: you might see where the ink squished or swirled in unexpected ways when pressed. Monoprints, which might use a pre-existing plate plus extra inking, can combine a known image (say a line drawing from an etching) with one-time coloration or texture on top.

Visually, monotypes and monoprints often have atmospheric textures and a sense of immediacy. They may lack the super sharp lines of an etched intaglio or the uniform fields of a screen print, but they make up for it in expressive, unique marks. No two monotypes are alike, and that uniqueness is apparent when you see them . They are often signed “1/1” in edition notation, meaning it’s an edition of one.

Tactile qualities

Because monotypes typically involve applying and transferring ink without deeply engraving or carving a plate, the prints generally feel flat on the paper.

The amount of ink can vary with some monotype techniques involve very thin films of ink, which leave almost no texture on the paper

Others might involve thicker applications or even collage elements that leave more texture. If the monotype was made by running through a press, you might feel a faint plate mark if a plate with edges was used, but often monotypes are hand-transferred, yielding no noticeable indentation.

The paper itself might show where ink was very heavily applied by a slight buckling or a tide line of pigment (especially with watercolor monotypes). In a monoprint that uses an etched or carved plate, you could feel some of the same textures as a regular intaglio or relief in places, combined with flatter printed areas elsewhere.

Overall, monotypes can be textural if an artist intentionally works thickly, but most have a subtle tactile presence creating a visual illusion that it’s a direct printing.

Examples

Many famous artists have explored monotypes for their expressive potential. Edgar Degas made monotype prints with black ink that he would then work over with pastels, creating richly textured images.

Contemporary printmakers often use monotype techniques to add background textures or colors behind other prints. For collectors, a monotype is appealing because it’s absolutely unique; it blurs the line between a print (which usually has multiples) and a painting or drawing (one of a kind).

Owning a monotype by an artist can feel like owning an exclusive piece of their work that no one else will have a copy of. However, because monotypes are unique, they are sometimes a bit outside the traditional print collector’s realm of editions and states. And they are valued more like singular artworks.

6. Collagraphy

Collagraphy (or collagraph) is a more experimental printmaking method where instead of carving into a plate, the artist builds up a collage on a plate and then prints from it. The word comes from “collage,” which hints at the process: artists glue various materials (paper, fabric, leaves, sand, string, or any textured objects) onto a sturdy plate (like cardboard, wood, or metal). This creates a highly textured plate with raised and recessed areas. Once sealed (often with varnish), this plate can be inked in different ways and run through a press to make a print.

Collagraphs can be inked relief style (ink on the top surfaces only) or intaglio style (ink in the recesses, wiping the top clean) or a combination of both. This makes collagraphy a very versatile hybrid technique.

Visual characteristics

Because collagraph plates can incorporate virtually any texture or material, the resulting prints are often richly textured and sometimes unpredictable.

Visually, a collagraph might show broad areas of tone and texture rather than fine lines. An artist might glue lace or sandpaper to the plate making the print to pick up the pattern of the lace or the grainy speckle of the sandpaper in the inked impression.

Collagraph prints can resemble relief prints if inked that way, or etchings if inked intaglio, but they often have a distinctively organic, collage-like look. There may be white speckles where textures prevented ink from touching the paper, or deep dark areas where ink pooled.

The style in collagraphy differs a lot. Some collagraphs look almost like photographs in tone (if carefully made and inked), while others are clearly rough and experimental. Color can be applied by using different ink colors on different parts of the plate or by printing multiple times.

Each collagraph print is sometimes unique, because the collaged plate can be inked differently each time or might even change (some delicate collagraph plates wear down or pieces fall off over multiple printings).

Tactile qualities

Collagraph prints often have a very deeply embossed texture. Because many collagraph plates are printed intaglio-style with a press, the soft paper is pushed into all the nooks and crannies of the collaged materials.

If you run your hand over a collagraph print, you might feel the hills and valleys corresponding to the collage elements. For example, places where a piece of fabric was on the plate might appear as a raised or depressed area on the print depending on inking. The edges of thick materials can emboss an outline into the paper.

Collagraphs inked in relief (surface ink) might have the collaged items leave white voids in the print that also have a physical depth on the paper. The overall tactile impression is often more dramatic than other print types. Collagraphs can almost feel like embossed paper art in addition to being ink prints. Collectors who enjoy texture are often drawn to collagraph prints because they combine printed ink with a sculptural paper quality.

Examples

Collagraphy is popular in contemporary printmaking workshops and among experimental artists. For example, artists might use collagraph techniques to mimic natural scenes by printing leaves and threads to create an image of a forest with actual leaf textures.

It’s also a favored technique for abstract, textural pieces. Since collagraphs are less standardized than other techniques, they’re less common in older, traditional print collections (old master printmakers didn’t use glue and cardboard in this way). But in modern print shows, you’ll often find at least one collagraph because of the unique effects it offers.

For an art buyer, a collagraph can be a fascinating piece that almost bridges into mixed-media territory, often available in very limited editions due to the plate’s fragility.

7. Digital Printmaking

Digital printmaking is the newest category on the scene, and it involves using computers and digital printers to create art prints. In digital printmaking, the “matrix” is a digital file where the artwork is created or scanned into a computer.

High-quality inkjet printers (sometimes called giclée printers in art) then spray microscopic droplets of pigment ink onto paper or canvas to produce the image. Because it’s driven by digital technology, this method can reproduce anything from photographs to digital illustrations with great accuracy.

While some traditionalists debate whether digital prints count as “printmaking,” many contemporary artists and publishers do consider them a legitimate technique especially when they are produced in limited editions on archival materials.

Visual characteristics

A well-made digital art print can be stunningly detailed and colorful. Modern giclée printers can produce millions of colors and very smooth gradients, so the resulting print might have a photographic realism or a flawlessly smooth color field which are hard to achieve in traditional print processes.

Visually, digital prints do not have the telltale signs of manual printmaking. There are no plate marks, no inky mis-registrations, no relief textures. Instead, the surface usually has a very even sheen of ink.

Under magnification (or very close up), you might see dithering or tiny dots from the printer, but high-end prints have extremely fine resolution. Digital prints can mimic the look of other art. For example, a digital print of a watercolor can look very much like the original watercolor painting in terms of color and tone. However, the absence of any texture from brush or print process gives it away.

One key visual feature is color richness: digital printing allows for vibrant color combinations and photographic quality imagery that traditional four-color printing (like lithography or screen) would struggle with.

Tactile qualities

Digital prints are usually quite flat to the touch. The ink from an inkjet printer is sprayed onto the surface in such fine layers that you generally cannot feel it. Unlike screen printing, where you can feel the thick ink, a digital print’s surface will feel like the paper itself (unless it’s an unusually heavy application or a specialty printer that applies texture).

If printed on a nice cotton rag paper or canvas, what you feel is mostly the paper’s texture (smooth, textured, canvas weave, etc.) without any added dimensionality from the printing process. There’s no embossing (no plate, no pressure), and the paper remains as flat as it was originally.

One tactile difference is that digital prints often use different papers than traditional prints. Printers of digital printmaking use very slick papers for photographs or special coatings. Hence, they might feel different from the matte fine art papers used in etching or lithography.

But if a digital print is on a high-quality art paper, to the touch it might be nearly indistinguishable from a lithograph or other print that also has an even layer of ink. It’s the look that differs more than the feel.

Examples

Digital printmaking is ubiquitous in photography (most fine art photographs these days are giclée or digital C-prints). It’s also used by artists who create digital art or who want to make prints of their paintings without the complexity of traditional printmaking.

Many illustrators release limited edition giclée prints of their work. For collectors, a digital print can be attractive because of its fidelity to the original image and often a lower price point compared to something like a hand-pulled etching (since once the digital setup is done, prints can be made on demand).

However, collectors also pay attention to the edition size and quality. A digitally printed edition should be limited and on par with archival standards to be valued in the art market. Some artists combine digital printing with traditional techniques, printing a base image digitally and then adding layers of screen print or etching on top, marrying modern and traditional methods.

So, What Should Art Collectors and Professionals Know

For art collectors and professionals, knowing the distinctions is crucial. A woodcut’s bold lines and occasional wood grain, an etching’s fine web of lines and telltale plate indentation, a lithograph’s smooth tonal washes, or a screen print’s vibrant layered colors are not just technical outcomes, but part of the character of the artwork.

Each print carries the history of its making in its appearance. You can almost visualize the carving of a relief block or the rocking of a mezzotint plate when examining those prints up close.

In practical terms, the tactile and visual nuances of prints also influence their market and care. Collectors often delight in the plate mark of an intaglio print or the slight raise of silkscreen ink, which are badges of authenticity and craftsmanship.

Museums and galleries, too, display prints with an eye to lighting and angle, because a raking light might reveal textures (like the depth of a collagraph or the sheen of a relief ink) that a frontal view might miss.

Technically, many of these printmaking methods can be combined or tweaked. Artists continue to experiment by using digital prints as a base and adding hand-printed layers, or mixing intaglio and relief on one piece. The field is alive, with new hybrids emerging, but the foundational categories remain as relevant as ever for describing how a print was made.

Whether you are a seasoned collector admiring the almost sculptural lines of an engraving, or an artist exploring which technique best suits your vision, knowing the types of printmaking deepens your engagement with the art. Each process brings its own visual language and texture.

From the earliest woodcuts that democratized art and knowledge to cutting-edge digital prints expanding what’s possible, printmaking is a testament to human ingenuity in art. It invites us to not only look at an image, but also feel the artist’s hand in every inked line and embossed contour. In the world of prints, understanding the technique truly enhances the joy of both creation and appreciation.